Up next: Micro-units and dorms for grown-ups?

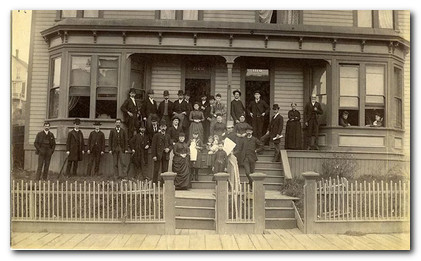

“Rental rates are out of reach for Michigan residents,” said a June 13 Community and Economic Development Association of Michigan (CEDAM) news release reporting the results of a new report by the National Low Income Housing Coalition (NLIHC).The report says that the market rate for a two-bedroom apartment in Michigan is $876 a month and to afford it a worker needs to make $16.85 an hour. The average renter’s wage is $14.27 per hour.“Insufficient affordable housing” doesn’t just mean housing for low-income people. In parts of Michigan -- and around the country -- it is the symptom of a mismatch between employer’s needs and the ability of workers to get to jobs. Traverse City has a tourism-based economy and charming, pricey residential neighborhoods in the city itself, forcing service industry workers to range far afield for reasonable rents. (Short term rentals [STR] of in-town units also reduce their availability for local workers. Our Dick Carlisle advocates for continuing to allow local governments to regulate STRs, in opposition to a bill that would move that authority to state government.)In 2016 the Michigan Association of Planning adopted a policy on housing. Among other solutions, the document advocates for the return of single-room-occupancy (SRO) uses, once known as boarding houses.As we see in this well-documented article, boarding houses -- predecessors to today's micro-units -- were a well-accepted housing option through the 1950s. After World War II, rising affluence expanded housing choices for workers and young people. Indigent and mentally ill people moved in, neighbors said, “Not in my back yard” and communities restricted or prohibited them.SROs are returning, though, in unlikely places and forms. In San Francisco, middle-income workers are moving into modern dormitories. Residents have a bedroom of 130 to 220 square feet and use a bathroom down the hall. They use common kitchens and enjoy organized activities and concierge-like services. They pay rent of $1,400 to $2,400, compared to the average one-bedroom apartment in the city at $3,300 a month.As reported in the November, 2011 edition of Planning, a Seattle developer built self-contained micro-units of a few hundred square feet, with a tiny kitchen and bath, renting for $500 per month. He charges tenants separately for parking. Palo Alto, CA housing corporation developed the Tree House, with 300- to 400-square-foot apartments renting for $400 to $900 a month, based on income.A cursory search of the communities served by Carlisle|Wortman Associates reveals few that permit single room occupancy. Royal Oak licenses them like hotels and requires establishments accepting tenants for long stays to comply with residential building codes.Permitting smaller apartments and reducing related parking requirements are only one of the many solutions to Michigan’s affordable housing problem. MAP’s housing policy offers a number of options:

“Rental rates are out of reach for Michigan residents,” said a June 13 Community and Economic Development Association of Michigan (CEDAM) news release reporting the results of a new report by the National Low Income Housing Coalition (NLIHC).The report says that the market rate for a two-bedroom apartment in Michigan is $876 a month and to afford it a worker needs to make $16.85 an hour. The average renter’s wage is $14.27 per hour.“Insufficient affordable housing” doesn’t just mean housing for low-income people. In parts of Michigan -- and around the country -- it is the symptom of a mismatch between employer’s needs and the ability of workers to get to jobs. Traverse City has a tourism-based economy and charming, pricey residential neighborhoods in the city itself, forcing service industry workers to range far afield for reasonable rents. (Short term rentals [STR] of in-town units also reduce their availability for local workers. Our Dick Carlisle advocates for continuing to allow local governments to regulate STRs, in opposition to a bill that would move that authority to state government.)In 2016 the Michigan Association of Planning adopted a policy on housing. Among other solutions, the document advocates for the return of single-room-occupancy (SRO) uses, once known as boarding houses.As we see in this well-documented article, boarding houses -- predecessors to today's micro-units -- were a well-accepted housing option through the 1950s. After World War II, rising affluence expanded housing choices for workers and young people. Indigent and mentally ill people moved in, neighbors said, “Not in my back yard” and communities restricted or prohibited them.SROs are returning, though, in unlikely places and forms. In San Francisco, middle-income workers are moving into modern dormitories. Residents have a bedroom of 130 to 220 square feet and use a bathroom down the hall. They use common kitchens and enjoy organized activities and concierge-like services. They pay rent of $1,400 to $2,400, compared to the average one-bedroom apartment in the city at $3,300 a month.As reported in the November, 2011 edition of Planning, a Seattle developer built self-contained micro-units of a few hundred square feet, with a tiny kitchen and bath, renting for $500 per month. He charges tenants separately for parking. Palo Alto, CA housing corporation developed the Tree House, with 300- to 400-square-foot apartments renting for $400 to $900 a month, based on income.A cursory search of the communities served by Carlisle|Wortman Associates reveals few that permit single room occupancy. Royal Oak licenses them like hotels and requires establishments accepting tenants for long stays to comply with residential building codes.Permitting smaller apartments and reducing related parking requirements are only one of the many solutions to Michigan’s affordable housing problem. MAP’s housing policy offers a number of options:

- Permit accessory dwelling units

- Lower floor area ratios

- Reduced minimum square footage

- Zone for cluster housing

- Use density as a residential zoning measurement (vs. “single family” or “multi-family”)

- While maintaining local codes and regulations, rehabilitate aging and substandard manufactured home communities

- Expand public transportation

There’s one other thing that communities may need to expand affordable housing: Courage. Elected officials who advocate for affordable housing will be challenged to educate their citizens about the societal benefits of providing housing for all.Coming up next: The role of missing middle housing in addressing Michigan’s housing deficiency